INTRODUCTION

Although most cases of episcleritis are idiopathic, an estimated 27% to 36% are associated with an underlying systemic condition.1,2 The most common etiologies are inflammatory, including rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody vasculitis. Less commonly, episcleritis is caused by infectious, neoplastic, and toxic sources.1,2

Under physiologic conditions, damaged and unneeded intracellular proteins are broken down by proteasomes. A key step in this process is the activation of ubiquitin, which is attached to unwanted proteins allowing for their detection and degradation by proteasomes.3 When these unneeded proteins build up, cellular functioning can be affected and the proteins themselves may be a target for an immune response.3,4 VEXAS syndrome is caused by an X-linked recessive mutation in the UBA1 gene within blood and immune progenitor cells in the bone marrow.5 The UBA1 gene codes for the ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1), resulting in an inability of proteasomes to degrade unwanted intracellular proteins.3,4 Because it affects blood and immune stem cells, most of the clinical features of VEXAS are hematologic and autoinflammatory.5 Histologically, biopsies of these abnormally functioning bone morrow cells show the presence of large intracellular vacuoles.6 The name VEXAS syndrome is a descriptive acronym that stands for vacuoles, E1 enzyme, X-linked, autoinflammatory, somatic mutation and was first described in 2020, with 25 men having atypical adult-onset inflammatory disease, myeloid dysplasia, and overlapping clinical features.5

This case report details a case of bilateral episcleritis caused by VEXAS syndrome. Written informed consent was obtained for identifiable health information in this case report.

CASE REPORT

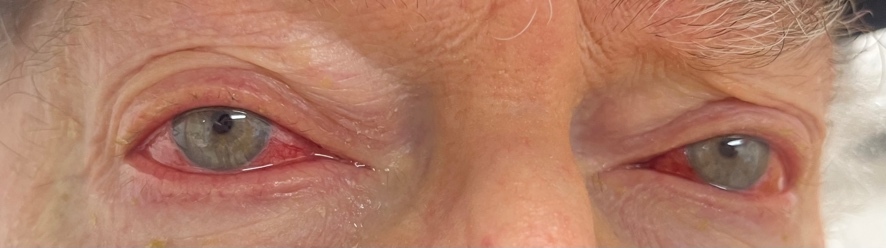

An 81-year-old White man was urgently referred from the emergency room for bilateral red eyes. He had been diagnosed with VEXAS syndrome 1 year prior by positive genetic testing for a UBA1 gene mutation after a suggestive clinical presentation and bone marrow biopsy that was inconclusive. During the disease course, his syndrome had manifested with cytopenia, macrocytosis, auricular chondritis, and an erythematous skin rash. The patient had presented to the emergency room with a 1-week history of frontal headache accompanied by bilateral eye redness (Figure 1). While in the emergency room, computed tomography imaging had been performed and did not show evidence of orbital inflammation or preseptal cellulitis.

Once in the eye clinic, he reported mild ocular pain without discharge. Best-corrected vision was 20/40 in both eyes, stable with his last eye examination 1 year prior and consistent with the previous diagnosis of cataracts. Slit lamp examination showed superficial bulbar conjunctival vessel injection of both eyes with no conjunctival follicles or papillae. The cornea was clear without sodium-fluorescein staining. There was no anterior chamber reaction. The conjunctiva was almost completely blanched with topical 2.5% phenylephrine. Once the pupils were dilated, the fundus showed mild nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy with a few blot intraretinal hemorrhages in the midperiphery. There was no vitritis or retinal vasculitis.

During his initial work-up for VEXAS syndrome and routine care by his internists, the patient had negative test results for other common causes of episcleritis, including antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody and antinuclear antibody testing, in addition to a recent upper endoscopy and colonoscopy that did not show evidence of inflammatory bowel disease. The patient did have a positive test result for rheumatoid factor. However, rheumatoid factor testing has been found to be positive in 6% to 7% of patients diagnosed with VEXAS syndrome.7 Furthermore, the rheumatology service evaluated the patient and did not see synovitis of the hands, wrists, elbows, shoulders, knees, ankles, or feet to suggest rheumatoid arthritis. Therefore, the positive rheumatoid factor test result was attributed to his VEXAS diagnosis.

Based on his eye examination findings and prior negative test results of common conditions that cause episcleritis, he was diagnosed with bilateral episcleritis secondary to VEXAS syndrome. After further questioning, the patient reported he was still taking the immunosuppressant Janus kinase inhibitor, ruxolitinib, but admitted to discontinuing his maintenance dose of 15.0 mg oral prednisone. His rheumatologist was consulted, and the patient was placed on 20 mg of oral prednisone and instructed to continue the ruxolitinib. Over the course of the next few weeks, the episcleritis resolved with continued oral prednisone usage (Figures 2-4).

DISCUSSION

VEXAS syndrome is rare, with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 13,591 individuals.8 This condition is acquired in adulthood, typically over the age of 50 years, and because it is X-linked, is primarily seen in men. The presence of monosomy of the X chromosome explains its infrequent occurrence in women.8 Affected patients most often present with recurrent fever and a combination of hematologic anomalies and inflammatory findings particularly affecting the skin, lungs, and cartilage of the ear and nose.5,8 The hematologic abnormalities of macrocytic anemia, cytopenia, and myelodysplastic syndrome have most frequently been reported.4 Skin rashes, including neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis and panniculitis, are common.9 Pulmonary findings, including lung infiltrates and pleural effusion, are frequently seen, as are auricular and nasal chondritis.4 The reported prognosis for VEXAS syndrome has been variable, with mortality rates ranging from 16% to 50% at 3 to 4 years.10,11 Genetic differences in the UAB1 gene mutation and the organ systems involved in the inflammation have been implicated as risk factors for higher mortality.11,12 The most common site for mutation of the UBA1 gene is at p.Met41, which is a translation initiation codon for the UBA1b protein.12 Common variants observed include p.Met41Thr, p.Met41Val, and p.Met41Leu.12 The variant with the highest prevalence for ocular manifestation is p.Met41Thr, which is the mutation in this patient.12 Patients with p.Met41Val are found to have the highest death rates compared with patients with the other 2 variants. In terms of organ system involvement, ear chondritis is associated with increased survival, whereas the development of transfusion-dependent anemia shows a decreased survival.12 The patient described in this case report had several common features of VEXAS syndrome, including an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, cytopenia, macrocytosis, auricular chondritis, and an erythematous papule-like skin rash of the neck (Figure 5). The punch biopsy of the skin rash revealed neutrophilic inflammation consistent with dermatologic findings seen in patients with VEXAS syndrome.

An estimated 16% to 46% of VEXAS patients have ocular involvement.4,13 Manifestations include inflammation of both the eye and periocular structures. In a 2024 review from an international VEXAS registry, periorbital edema was the most common eye diagnosis, being present in 30% of those with ocular findings. This was followed by episcleritis and scleritis, both found in 19% of VEXAS patients.13 Less frequently seen were uveitis (15%), conjunctivitis (15%), blepharitis (11%), and orbital inflammatory disease (7%).13 Other smaller case series have reported dacryoadenitis, cranial neuropathy, inflammatory optic neuritis, and retinal vasculitis, but these diagnoses are less common.4 From a systematic review, of the cases that reported on the laterality of ophthalmic involvement, 65% were bilateral presentations.14

Currently, there is no standard of care in the diagnosis of patients with VEXAS syndrome. Typically, the combination of characteristic systemic findings, abnormal inflammatory laboratory results, blood dyscrasia, genetic testing for the UBA1 gene mutation, and biopsy evidence of bone marrow cell vacuoles are used in the diagnosis.6,15 Suspicion of VEXAS syndrome should be heightened in patients who are male and older than 50 years who present with the constitutional symptom of fever, along with evidence of systemic inflammation, particularly of the skin, lungs, and cartilage of the ear and nose.15 In patients diagnosed with periorbital edema, episcleritis, or scleritis, a positive review of systems suggestive of VEXAS syndrome should result in ordering a complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and computed tomography of the chest.13,15 If results remain suggestive, bone marrow biopsy to detect vacuolization and genetic testing for the UBA1 gene are considered pathognomonic for the diagnosis.6,16

Although not curative, corticosteroids are the initial treatment of choice for patients with VEXAS syndrome. A starting daily dose of 20 mg or more of oral prednisone is typically effective in alleviating systemic inflammatory symptoms.17] However, manifestations frequently recur when tapering of steroids is attempted, and their side effects often will not allow for their long-term use. Therefore, steroid-sparing agents are often required, but support for their use comes from case reports and small case series, not large randomized clinical trials (Table 1). In addition to pharmacologic treatments, intravenous immunoglobin therapy has been reported as a treatment for VEXAS syndrome in combination with other drugs.17 The only potentially curable treatment that addresses the underlying pathophysiology of VEXAS is allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. In this procedure, healthy donor bone marrow is collected, most commonly from the iliac crest, and infused into the patient with VEXAS syndrome.18 The proposed mechanism is to replace the mutated UBA1 clone with healthy cells to prevent clonal hematopoiesis.19 Unfortunately, stem cell transplantation is not without potentially significant side effects, including initial infections and graft vs host disease in the long-term.20

CONCLUSION

The current standard of care for episcleritis is to not work up typical initial presentations. Recurrent or atypical presentations should raise suspicion of an underlying systemic cause. In those instances, a thorough case history often directs ancillary testing. When VEXAS syndrome is the underlying cause of episcleritis, a combination of constitutional symptoms, in addition to hematologic and inflammatory findings, may be present.

-

No identifiable health information was included in this case report

-

The author declares no conflicts of interest

-

The author declares no funding sources

TAKE HOME POINTS

-

Although most cases of episcleritis are idiopathic, approximately one-quarter to one-third are associated with an underlying systemic condition.

-

VEXAS syndrome is a newly recognized disorder caused by a gene mutation in hematopoietic stem cells that results in blood dyscrasia and widespread aberrant inflammation particularly of the skin, lungs, and cartilage of the ear and nose.

-

Up to almost 50% of patients with VEXAS have ocular findings, most commonly periorbital edema, episcleritis, and scleritis. Rarely, uveitis, conjunctivitis, blepharitis, and orbital inflammation are seen.

-

VEXAS syndrome should be considered in cases of episcleritis that are accompanied by constitutional symptoms, inflammatory signs, and hematologic abnormalities.