INTRODUCTION

Less than 1% of all eyelid malignancies are metastatic lesions, most often originating from malignancies in the breast, skin, gastrointestinal tract, respiratory tract, and genitourinary tract.1–3 Tarsal or palpebral conjunctival metastases are exceedingly rare, with the largest case series of 10 patients by Kiratli et al including only 2 patients with palpebral conjunctival metastases.4 Because of its rarity, reports of tarsal conjunctival metastases are often limited to individual case reports or grouped with other metastatic eyelid lesions. Metastatic lesions to the eye or adnexa can indicate widespread malignancy, with Riley et al reporting multiorgan metastases in nearly three-quarters of patients with metastatic tumors of the eyelid.1 The frequency of ocular metastases are increasing with improved treatments and survival rates but remain relatively rare, affecting less than 5% of all people with systemic malignancies.5,6

Ocular metastases from neuroendocrine neoplasms are even more rare, generally affect the uveal tract or orbit, and less commonly involve the eyelid.7,8 Neuroendocrine cells can be found throughout the body, but neuroendocrine neoplasms most commonly originate in the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts. Metastatic disease is present at the time of diagnosis in roughly one-fifth to one-quarter of all cases of neuroendocrine tumors, with the most common sites of metastasis being the liver, lymph nodes, and bones.9–11

This report highlights a rare case of tarsal conjunctival metastasis from a neuroendocrine tumor of unknown primary origin revealed through a detailed eyelid examination. No identifiable health information was used in this case report.

CASE REPORT

A 76-year-old White man presented to the eye clinic with a red and painful right eye for the past 10 days. Symptoms included photophobia, watery discharge, matted eyelids in the morning, and extreme foreign body irritation along with a feeling of fullness of the upper lid. The patient’s medical history was significant for gastroesophageal reflux disease, hypertension, and metastatic neuroendocrine tumors involving the liver and bones, which had been diagnosed 7 years before this examination. He was taking 20 mg omeprazole for his reflux and 25 mg daily of spironolactone for his hypertension. The neuroendocrine tumors had been treated with hepatic artery chemoembolization shortly after diagnosis and with monthly injections of octreotide and desonumab to control the associated carcinoid syndrome and cancer-induced bone destruction, respectively. The patient had also completed a course of lutetium-177–dotatate treatment 2 years before this examination when worsening of the liver and bone metastases was noted on gallium-68-peptide DOTATATE positron emission tomography/computed tomography.

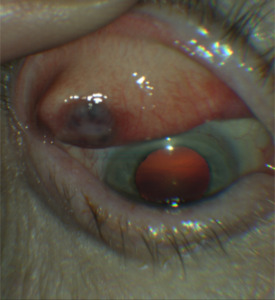

On examination, his best-corrected Snellen acuity was 20/20 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left eye. His pupils were round, equal, and reactive without an afferent pupillary defect. His confrontation visual fields were full in each eye and his intraocular pressures were measured as 12 mm Hg in the right eye and 10 mm Hg in the left eye with Goldmann tonometry. On slit lamp examination, external assessment was grossly unremarkable without redness or cutaneous lesions of the eyelids, but mild diffuse fullness of the right upper eyelid was noted. Upon eversion of the right upper lid, the patient was found to have an elevated, discolored nodular lesion of the tarsal conjunctiva. The nodule was 1 cm in diameter, black, and raised with indistinct margins. The surrounding palpebral conjunctiva was injected (Figure 1). The patient’s pupils were then dilated, and his posterior segment examination was unremarkable.

To alleviate the conjunctival injection and foreign body sensation, the patient was prescribed tobramycin 0.3%/dexamethasone 0.1% and carboxymethylcellulose 1% 4 times daily to the right eye. A follow-up examination 1 week later revealed the palpebral conjunctival injection surrounding the nodule had improved and his pain had resolved, but the size of the nodule remained unchanged (Figure 2). The patient was referred to an oculoplastic specialist for evaluation, with the patient experiencing worsening of the perceived fullness and subsequent drooping of the right upper lid in the intervening time before an excisional biopsy of the lesion was performed. The pathology report confirmed a low-grade neuroendocrine tumor, and the biopsy results were communicated to the patient’s oncologist who subsequently added capecitabine and temozolomide to the treatment regimen.

One year later, an examination in our clinic revealed complete resolution of the patient’s symptoms and no recurrences or new eyelid lesions (Figure 3). The patient’s disseminated neuroendocrine tumors were considered stable by his oncologist after the change in his medical therapy.

DISCUSSION

Neuroendocrine cells are innervated epithelial cells dispersed throughout the body and make up the diffuse neuroendocrine system. These cells express markers and peptides associated with the central nervous system and have the ability to secrete hormones. The neuroendocrine system regulates and coordinates bodily functions that maintain homeostasis.12

Characteristics

Neuroendocrine neoplasms are divided into the more common well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors and the more aggressive poorly-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas, which includes Merkel cell carcinomas.9,12–15 Neuroendocrine tumors can be classified into low, intermediate, and high grades based on the histological appearance and proliferation rate from miotic counts and Ki-67 index, with Ki-67 being a protein that is found in actively dividing cells.12,14 Approximately 20% to 30% of neuroendocrine tumors are functional, secreting excess amounts of peptide hormones (eg, serotonin, histamine, tachykinins, prostaglandins).8,16,17 This overexpression of hormones can cause carcinoid syndrome, which includes symptoms of facial flushing, diarrhea, and heart disease. The liver inactivates these hormones under normal circumstances; therefore, carcinoid syndrome commonly occurs after metastasis to the liver.10,12,17 This patient was experiencing facial flushing after eating and diarrhea for 6 to 8 months before the discovery of metastatic neuroendocrine tumors in the liver and bones. This patient also had markedly elevated levels of 24-hour urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic during the initial diagnostic workup, which is highly specific for serotonin-producing neuroendocrine tumors.10,14,18

Improvements in imaging and histopathology techniques have resulted in earlier detection and hence increased the reported incidence of neuroendocrine tumors, but diagnosis can still be challenging due to the indolent nature and sometimes nonspecific clinical presentation. Even so, the detection of biochemical markers in the blood and urine, such as the aforementioned 5-hydroxyindoleacetic, chromogranin A, and neuron-specific enolase can indicate the presence of neuroendocrine neoplasms.10 Monitoring circulating serum chromogranin A can be useful to assess for treatment response and disease activity and has been routinely monitored in this patient as a correlate to imaging and symptomatology to assess for treatment response and disease progression. Computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, ultrasonography, and endoscopy can assist in visualization of lesions.10,14,17 Neuroendocrine neoplasms often overexpress somatostatin receptors; therefore, use of somatostatin receptor-targeting radiotracers with imaging, such as gallium-68-peptide DOTATATE positron emission tomography/computed tomography, have been shown to be beneficial in detecting smaller occult lesions.12,14,19 Our patient had liver and bone metastases visible on initial computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging scans, as well as widespread metastatic disease in the skeleton, liver, lymph nodes, and scrotum, subcutaneously seen on gallium-68-peptide DOTATATE positron emission tomography scans obtained throughout the course of his care.

Generally, neuroendocrine tumors arise from the gastrointestinal tract, tracheobronchial tree, thymus, parotid, breast, ovary, and testis. The primary site of neuroendocrine tumors is unknown in 10% to 14% of cases, and many cases become symptomatic only after metastasis to the liver.8,10,11,13,14,17 The primary tumor site in this case has not been determined.

Metastasis to the Eye

Ocular metastatic disease arising from embolic malignant cells is most common in the densely vascularized uveal tract, with the vast majority of cases occurring in the choroid followed by the iris and ciliary body.5,8 Eighty-five percent of orbital metastases originate from gastrointestinal malignancies, whereas uveal and intraocular metastases tend to originate from malignancies in the bronchopulmonary and tracheobronchial tracts, respectively.20

Eyelid metastases are far less common and account for less than 1% of all malignant eye lesions.1–3,6 Metastatic eyelid lesions typically occur in patients with known multiorgan systemic cancer or other ocular tissue involvement. A retrospective review of 20 patients with eyelid metastases completed by Bianciotto et al showed that the upper eyelid was the most common site of metastases (35%) and the majority of lesions involved only the subcutaneous tissue (85%), with only 1 patient demonstrating a metastatic lesion of the tarsal conjunctiva similar to this case.21 Eyelid metastases are categorized into nodular, inflammatory/infiltrative, or ulcerative forms.1,22,23 Nodular is the most common form, typically with a painless solitary nodule being the presenting symptom in 60% of cases.21,23 The metastatic lesion in this case was a nodular lesion.

When assessing for potential ocular metastasis, comprehensive evaluation of the external and internal ocular structures may necessitate use of gonioscopy while B-scan ultrasonography can be used to further evaluate retinal lesions.20 Diplopia and/or proptosis may suggest orbital involvement; therefore, computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging scans of the orbits should be performed.19 As our patient was routinely imaged for metastatic lesions and did not have diplopia or proptosis, further imaging was not ordered.

Due to the possibility of metastatic disease, it is very important to perform histopathological analysis on all excised eyelid lesions. Patients with eyelid metastasis tend to have a low survival rate, with one case series showing 67% survival at 9 to 12 months.21

Differential Diagnoses

The differential diagnoses for eyelid neoplasms range from benign lesions, such as chalazia and cysts to malignant carcinomas. Basal cell carcinomas are by far the most common, accounting for 90% of eyelid malignancies, followed by squamous cell carcinoma, sebaceous carcinoma, melanoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma.24

One important differential diagnosis to consider is Merkel cell carcinoma. Merkel cell carcinoma is an aggressive tumor of epithelial and neuroendocrine origin with a predilection toward older White individuals.25–27 The head, neck, and upper limbs are the most common site of Merkel cell carcinomas, with the eyelids accounting for only 2.5% of cases.27 Merkel cell carcinoma are commonly mistaken for chalazia or basal cell carcinomas and appear as solitary, red, and violaceous skin lesions with overlying telangiectasias.26 If found on the eyelid, they are more commonly found in the middle layer of the upper eyelid, in contrast to basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinoma, which are commonly found on the lower eyelid.25,27 In general, Merkel cell carcinoma eyelid lesions occur in women 2 times more than men. Periocular Merkel cell carcinoma is most commonly found on the eyelid and to a lesser extent can be found on the conjunctiva, lacrimal gland, iris, and orbit.25,27

Definitive diagnosis of malignant eyelid lesions is typically made with histology and immunohistochemical analysis. Histological appearance and proliferation rate can be helpful in grading the tumor but is often not specific enough on its own for definitive diagnosis. Immunohistochemical markers needed for the diagnosis of neuroendocrine differentiation include chromogranin A and/or synaptophysin, as well as less specific markers such as neuron specific enolase and CD56. Keratin markers AE1 and AE3 establish that the neuroendocrine tumor is epithelial in nature.28 Merkel cell carcinoma is a high-grade tumor of neuroendocrine epithelial origin and therefore will often express chromogranin A, synaptophysin, and AE1/AE3. The most common marker to differentiate Merkel cell carcinoma from other neuroendocrine neoplasms is cytokeratin 20, as well as negativity for CK7, S100, and thyroid transcription factor protein 1.25–28 Immunohistochemical markers can also be helpful in determining the primary site of the neuroendocrine neoplasm. For example, expression of caudal-type homeobox transcription factor 2, thyroid transcription factor protein 1, or islet 1 suggests midgut, lung, and pancreatic origins, respectively.14,28 The biopsy of the eyelid lesion in this case showed a low-grade tumor that strongly expressed AE1/AE3, chromogranin A, and synaptophysin consistent with a metastatic neuroendocrine tumor.

Treatment

Treatment of metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasms of the ocular structures often includes local and systemic approaches, depending on the extent and characteristics of the disease.20 Eyelid metastases can be treated with excisional biopsy, external beam radiotherapy, and/or systemic chemotherapy/immunotherapy.8,21,23

Surgical resection of neuroendocrine neoplasms is the only curative treatment available, but primary tumor resection is not always possible in widespread metastatic disease or occult lesions.9,13,16,17,29 In many cases of advanced neuroendocrine neoplasms, the goal of systemic therapy is stabilization of tumor growth and progression-free survival.30 As such, the majority of patients are treated based on the primary tumor origin (if known), aggressiveness, and functional hormone-excess-state.16 Chemotherapy and interferon treatment have been used to control the growth of aggressive neuroendocrine tumors; however, the treatment effect takes weeks and does not control the hormone-excess-state.16,31

More commonly, treatment involves drugs targeted toward the particular characteristics of the neuroendocrine tumors, such as somatostatin analogs or peptide receptor radionuclide therapy such as lutetium-177 dotatate. Once stabilized, patients should be monitored every 3 to 6 months with labs and imaging, then every 6 to 12 months once stable for at least 7 years.32

Short- and long-acting somatostatin analogues, such as octreotide and octreotide-LAR (SANDOSTATIN), are used to control the hormone-excess-state and subsequent carcinoid syndrome symptoms of flushing, diarrhea, and carcinoid heart disease.16,29 These drugs target the overexpression of somatostatin receptors by neuroendocrine tumors and delivering cytotoxic doses to the malignant neuroendocrine tumors.16,29 This patient was initially treated daily with short-acting octreotide for 2 weeks, followed by monthly long-acting octreotide-LAR.

Lutetium-177 dotatate is a radiolabeled somatostatin analogue that specifically targets tumor cells expressing the somatostatin receptors to deliver ionized radiation.33,34 In patients with neuroendocrine tumors originating from the mid-gut, it has shown longer overall survival rates with fewer toxic side effects compared with high-dose octreotide-LAR.33 Due to worsening bone and liver metastases, this patient completed a course of lutetium-177–dotatate infusions of 4 sessions separated by 8 weeks, with octreotide-LAR not administered within 28 days prior to the infusion per recommended protocol.

Approximately 2 months after the patient’s initial diagnosis of metastatic neuroendocrine tumor, a large 8-cm liver lesion was treated with hepatic artery chemoembolization with the co-administration of the chemotherapeutic agent, doxorubicin. Transarterial chemoembolization delivers cytotoxic chemotherapy to the highly vascularized tumor, which can reduce tumor volume and hormone production in unresectable liver metastases. Other liver-directed therapies in advanced liver metastases include transarterial embolization/radioembolization, radiofrequency ablation, and microwave ablation, which may be used in conjunction with surgical debulking and somatostatin analogues/peptide receptor radionuclide therapy.16,17,35

Bone metastasis of neuroendocrine neoplasms is considered a rare and late event, occurring after liver metastasis. Treatment of bone metastases of neuroendocrine neoplasms with bisphosphonates (ie, zoledronic acid) or receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand inhibitors has been shown to reduce skeletal-related events (eg, bone pain, fractures, spinal compression, and hypercalcemia) and improve overall survival.36,37 Denosumab is a receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand inhibitor therapy that blocks the formation of osteoclasts, cells that degrade type 1 collagen, resulting in the bone resorption/remodeling and subsequent formation of bone metastasis.36 This patient, having had bone metastases at initial diagnosis, was started on monthly denosumab injections shortly after undergoing transarterial chemoembolization.

The presence of the new eyelid lesion indicated progression of the patient’s metastatic neuroendocrine tumor, leading his oncologist to change his treatment to capecitabine and temodar. The combination of capecitabine and temodar is a standard chemotherapy in advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and has proven to be effective in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors of gastrointestinal, lung, and unknown origin.38 One year after the change in treatment, his disease was considered stable by his oncologist.

CONCLUSION

Less than 1% of all eyelid malignancies are metastatic lesions. In these cases, patients usually have a known multiorgan systemic cancer making a histopathological examination on all excised eyelid lesions imperative. Eversion of the eyelid of a patient with foreign body sensation is crucial for detection of potentially significant ocular and systemic findings. Treatment of cancer requires interprofessional communication and coordination between multiple areas of medicine. With this patient, the identification of a metastatic lesion on the eyelid led to a change in his systemic therapy and stabilization of his disease.

TAKE HOME POINTS

-

Make sure to evert the eyelid in all cases of a red eye.

-

A thorough medical history should be obtained so a possible etiology of any eyelid lesion can be ascertained.

-

Be mindful to collaborate with other treating providers so they are aware there is progression of the systemic condition.