INTRODUCTION

Anemia is a very common condition in both adult and pediatric populations.1–5 The cause can be unifactorial or multifactorial, which can make diagnosis and workup challenging.5 Most likely present in cases of severe anemia or concurrent thrombocytopenia, anemic retinopathy manifests with retinal ischemia, retinal edema, and hemorrhages at any level.1–4 Here, a case of acute microcytic anemia in an adult will be reviewed: including optical coherence tomography imaging, complete blood count, and an overview of the necessary systemic workup.

CASE REPORT

A 60-year-old White man presented for a comprehensive eye examination. His previous eye examination was 1 year prior. Findings from his most recent examination included mild hyperopic refractive error, mild nuclear sclerosis with 20/20 vision in both eyes, and a stable retinal pigment epithelium window defect in the posterior pole of the left eye without visual consequence. His systemic history was remarkable for newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus 1 month prior. His hemoglobin A1c at diagnosis was 7.4%, and the night before the current appointment, his fasting blood sugar level was measured at 134 mmol/L. In addition to diabetes, his health history included hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obstructive sleep apnea, atrial fibrillation, and mitral regurgitation. Current medications included metformin, metoprolol, budesonide, warfarin, aspirin, and rosuvastatin. He reported adherence to his medication and follow-up schedules outlined by his primary care physician.

Three days prior to his eye examination, the patient had called his primary care physician with complaints of new onset fatigue, dizziness, and shortness of breath. The patient was told this was likely attributable to his recent diagnosis of diabetes, and an outpatient appointment was scheduled in 2 weeks. However, general observation of the patient revealed that he was not well when he presented for his eye examination. His complexion was severely pale. Extreme shortness of breath made it difficult for him to walk the short distance to the examination room without the assistance of guardrails.

Best-corrected distance visual acuity was 20/30 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left eye. No change in refractive error was noted. Pupillary response, extraocular motility, and confrontation fields were unremarkable in both eyes. Significant conjunctival pallor and mild nuclear sclerotic cataract were noted on anterior segment examination. Intraocular pressure was 8 mm Hg in both eyes by Perkins applanation tonometry.

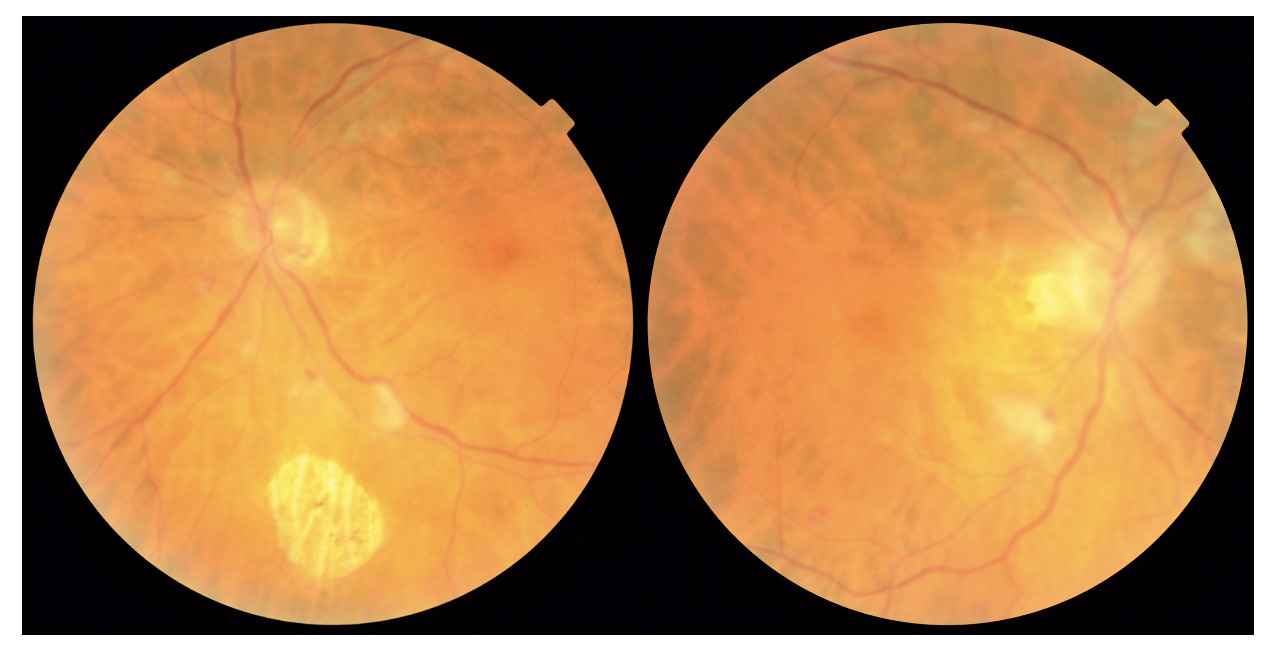

Dilated fundus examination revealed bilateral cotton wool spots that were present throughout the posterior pole but concentrated in the peripapillary area. This was worse in the right eye. Several small intraretinal hemorrhages were also noted along with Roth spots in both eyes. Optic nerve edema did not appear to be present, but peripapillary cotton wool spots made clinical evaluation of the disc challenging. There was no neovascularization of the disc or elsewhere. The macula was flat and clear in both eyes. There was mild bilateral arteriolar attenuation and pallor. The peripheral retina was unremarkable in both eyes. Fundus photography and optical coherence tomography images were acquired that day (Figures 1 and 2). Optical coherence tomography of the retinal nerve fiber layer exhibited marked edema of the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer with dilatation of the blood vessels clearly seen within. In the right eye, a sharp increase in peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer represents an acute large cotton wool spot abutting the disc. Overall, inner and outer retinal layers appear more disheveled in the right eye, as the level of retinal edema was likely more significant than the left. Although the retinal nerve fiber layer global values were the same between eyes.

Given retinal findings, blood pressure was checked in office with concern for hypertensive crisis. However, the patient was actually hypotensive (88/52 mm Hg). The patient became increasingly fatigued during the examination, and it became necessary to escort the patient by wheelchair to the emergency department in this multidisciplinary setting. The patient’s pale appearance in combination with fatigue, shortness of breath, and a retinopathy dominated by cotton wool spots raised concern for severe anemia. However, other blood dyscrasias or malignancies could not be ruled out.

A complete blood count was ordered and showed a very severe microcytic anemia with a hemoglobin value of 4.0 g/dL (normal range: 14-17 g/dL). See Table 1 for the full complete blood count readout. His last complete blood count was run over a year prior and had normal counts. There had been no previous diagnosis of anemia. With this finding of acute anemia, the patient was admitted for 1 week and received 5 blood transfusions. A full gastrointestinal workup (upper and lower endoscopy) was performed but no contributory pathology was identified. The patient left against medical advice after 1 week and was scheduled for an outpatient gastrointestinal consultation to continue the investigation. After discharge, his hemoglobin value had increased to 8.3 and the patient was feeling much better. An abbreviated eye examination performed prior to discharge showed significant improvement in his vision (20/20 in the right and left eye) as well as retinopathy (see Figure 3). The retinal hemorrhages were lighter and resolving in both eyes. Most obviously, the peripapillary region in both eyes appeared much more distinct with the resolution of the majority of the cotton wool spots in both eyes.

The patient continued to take the standard dose of prescribed ferrous sulfate 325 mg 3 times daily after his discharge. On this iron supplementation, the patient’s hemoglobin levels normalized over the next month. The patient was diagnosed with acute severe microcytic anemia, but the cause of this condition was not identified. The patient declined further workup. A 1-month follow-up with optometry revealed complete resolution of the retinopathy in both eyes (see Figure 4). Red blood cell counts remained mildly decreased, and to this point, the patient has experienced no further complication. No identifiable health information was included in this case report.

DISCUSSION

Anemia is diagnosed based on a reduction of 1 or more of the 3 main red blood cell markers obtained as part of a complete blood count: hemoglobin, hematocrit, or red blood cell count. Parameters and diagnosis of anemia can vary based on multiple factors including age, sex, pregnancy, smoking, altitude, and other drugs or medications.6,7 Hemoglobin value is typically used as the standardized diagnostic indicator of anemia. However, given variability in the parameters above, there is no true “gold standard” marker for diagnosis. The World Health Organization criteria for anemia in adult males is hemoglobin levels less than 13 g/dL and in adult females a level less than 12 g/dL.8 Finding a cause of the anemia can be even more challenging, as multiple diseases can lead to this condition. This discussion will focus primarily on adult patients and the workup for cases of microcytic anemia.

Anemia can have many causes. A reduction in red blood cell markers may result from insufficient or abnormal production of red blood cells in the bone marrow, blood loss, red blood cell destruction (hematolysis), or poor nutrition or absorption in the gastrointestinal tract.3 Symptoms may include weakness, fatigue, headaches, shortness of breath, gastrointestinal disturbances, and headache. Iron deficiency is the most common cause of anemia in adults. Other types of anemia include vitamin B12 deficiency or folate deficiency anemia, hemolytic anemia, sickle cell anemia, malignancy, or anemia of chronic disease (often infection or inflammation of the liver or kidney).6,7

In the eye specifically, anemic retinopathy results from retinal hypoxia.3,4 Hypoxia results in cotton wool spots and retinal edema. In addition, vasodilation results in increased transmural pressure and microtrauma to vessel walls that can lead to retinal hemorrhages at any level of the retina or choroid.1–4 Retinal edema related to hypoxia and an increase in choroidal thickness likely due to vasodilation have been documented as standard optical coherence tomography findings in anemia as well, worsening with the severity of the anemia.4 Roth spots are a common finding, with the white center being a result of retinal nerve fiber layer infarction. Vision loss is possible, most commonly due to hemorrhage or exudation within the macula. In rare or prolonged cases of anemia, optic neuropathy can occur.1–4 Although the literature varies, the general consensus is that anemic retinopathy occurs primarily in cases of severe anemia with hemoglobin values less than 8 g/dL and almost definitely in cases with values less than 6 g/dL.1–3 Thrombocytopenia can promote retinopathy in cases of anemia, but thrombocytopenia alone is not a risk factor for retinopathy.1 Our patient’s entering hemoglobin value of 4.0 g/dL correlates to the level of retinopathy that was observed. He did not, however, have concurrent thrombocytopenia. Clinicians need to recognize that it is very rare to find hemorrhages and cotton wool spots from anemia in mild to moderate cases and probe for other potential causes.1

A general understanding of the complete blood count is essential for primary care optometrists to help categorize hematological disease and associated eye findings. Cotton wool spots or retinal hemorrhages in the absence of a diagnosis of diabetes or hypertension warrants further investigation, and a complete blood count provides a great deal of information on overall hematologic status. Besides hematocrit, hemoglobin, and red blood cell counts, the other red blood cell markers included on a complete blood count are mean corpuscular volume, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, and red cell distribution width.9 Mean corpuscular volume is the average size of the red blood cells. This can be measured or calculated and is often used to classify anemia.9 Classifying the anemia as microcytic (low mean corpuscular volume), normocytic, or macrocytic (high mean corpuscular volume) can aid in differentiating its cause. Iron deficiency tends to be a microcytic anemia, as is seen in our patient. Macrocytic anemia is characteristic of vitamin deficiency anemias, like B12 or folate deficiency. Mean corpuscular hemoglobin is the average hemoglobin content in a red blood cell. Higher hemoglobin content allows for higher oxygen capacity and therefore more “chromicity.” Anemia is also classified as hypochromic (low mean corpuscular hemoglobin), normochromic, or hyperchromic (high mean corpuscular hemoglobin). Iron deficiency is the most common cause of hypochromic anemias, whereas hyperchromic anemias are rarer. The mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration is a ratio of mean corpuscular hemoglobin to mean corpuscular volume (in g/dL). Red cell distribution width reports the percentage variation in red blood cell size.9 The complete blood count includes a single white blood cell parameter; ordering a complete blood count with differential provides additional information on the concentrations of various types of white blood cells present in the sample. Platelet count or platelet size (mean platelet volume) are also reported on the traditional complete blood count.9,10 Hematologists can evaluate further by ordering a peripheral blood smear for more specific diagnostic criteria. An interprofessional team is often best for evaluating hematological disease.9,10

In this case, an adult male patient with severe microcytic hypochromic anemia was evaluated. The leading cause of microcytic anemia in adults is iron deficiency, and more specifically blood loss from a gastrointestinal bleed.11 An urgent gastrointestinal workup is appropriate in cases of new onset microcytic anemia in adults. Causes could include but are not limited to colon cancer, esophagitis, peptic ulcers, inflammatory bowel disease, small bowel tumors, or gastrointestinal vascular ectasias.11 For investigation, evaluation of the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract is performed, most commonly by upper endoscopy and colonoscopy. Video capsule endoscopy or computed tomography enterography can also provide further visualization of the tract.11 In our patient’s case, the workup was inconclusive. He was scheduled for an additional outpatient gastrointestinal workup. Iron supplementation was started, and his blood count remained stable, albeit still anemic, over the course of the next few years. Unfortunately, a full evaluation has yet to be completed. Iron supplementation can mask the underlying cause of anemia, and concern for malignancy or other nutrient malabsorption remains high. Continuing to encourage primary care and specialist visits with this patient is of utmost importance.

CONCLUSION

Often, the ocular presentation of anemia does not represent a sight-threatening emergency but gives insight into a potential systemic emergency. In this case, increasing red blood cell counts even mildly through blood transfusions resulted in resolving retinal findings within 1 week and full resolution in 1 month. Understanding the complete blood count and systemic management of this common condition is essential for optometrists to deliver potentially lifesaving care and highlights their role in primary health care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to acknowledge the mentorship of Muriel M. Schornack, OD, as a writing adviser through the Flom Leadership Academy of the American Academy of Optometry.