INTRODUCTION

Sensory strabismus, also known as secondary strabismus, is a type of strabismus resulting from poor vision. The vision loss is typically unilateral1 but can be bilateral and asymmetric.2 Although visual acuity is reported to range from 20/60 to light perception,3 the degree of monocular visual impairment is usually significant. Common causes include unilateral cataracts, optic nerve anomalies, corneal opacities, keratoconus, retinal disease, and significant uncorrected anisometropia.3–7 The eye is thought to drift because poor vision is an obstacle to sensory fusion.1,8

The direction of the strabismus can be horizontal, vertical, or torsional, with esotropia and exotropia being the most common forms.2 Some believe that the age of onset of vision loss influences the direction of the strabismus,3 although opinions vary on whether early vision loss predicts esotropia or exotropia.2,3,9 Most literature suggests that esotropia and exotropia are encountered with almost equal frequency when vision loss occurs before 5 or 6 years of age, whereas exotropia predominates in older children and adults.3,9 A dissociated vertical deviation4,10 or a vertical deviation caused by an overacting oblique muscle3,10 may accompany the horizontal deviation.

In managing sensory strabismus, one must address whether vision can be restored in the affected eye(s) and whether sensory fusion can be reestablished. If the vision loss is irreversible and reestablishment of fusion is not possible, treatment is typically limited to improving the cosmetic appearance of the eyes with extraocular muscle surgery. However, the prognosis for a successful long-term alignment after surgery is usually poor because of the lack of sensory fusion potential.1,11,12 Herein, we report a case of a young woman with sensory exotropia and severe bilateral vision loss who was treated with a novel vision therapy approach that improved the cosmetic appearance of her sensory exotropia. Written informed consent was obtained for identifiable health information included in this case report.

CASE REPORT

A 24-year-old female was referred by a local optometrist for an evaluation of a constant left exotropia that the patient found cosmetically displeasing. The patient reported that her exotropia was first noted at 10 years of age. She reported having had surgery for the eye turn when she was 16 years old, which initially straightened her eyes; however, over time, her left eye gradually drifted outward. The patient noted that she was previously fitted with a prosthetic contact lens to improve the cosmetic appearance of her exotropia. Unfortunately, the lens did not make her eye look straighter, so she discontinued wearing it.

Ocular history was significant for long-standing visual impairment due to cone-rod dystrophy. According to the referring optometrist’s records, the patient had decreased visual acuity that had remained stable since she was 10 years old (right eye 10/125 and left eye 5/80). The patient used several low-vision devices for reading and writing. Her general medical history was unremarkable. She had recently completed a master’s program in clinical psychology and needed 3000 hours of counseling experience for licensure. Her goal was for her eyes to appear aligned in photographs and during certain social- and work-related situations, using any treatment other than strabismus surgery.

The patient did not wear a refractive correction. Unaided distance visual acuities (Snellen) were right eye 20/250 and left eye 20/320 with no improvement with pinhole; unaided near visual acuities (reduced Snellen equivalent) were right eye 20/100 and left eye 20/200. Subjective refraction and best corrected distance visual acuity was right eye -0.50 DS (20/250) and left eye +1.00 -2.00 x 175 (20/320).

Cover testing without correction revealed a comitant, constant left exotropia of 30∆ to 35∆ at distance and near. Versions were full with end-gaze nystagmus noted. Correspondence was evaluated using the synoptophore (major amblyoscope), red lens test for correspondence, and Hering-Bielschowsky afterimage test. Paradoxical type-1 anomalous correspondence was present based on synoptophore testing (objective angle of 20∆ base-in, subjective angle of 20∆ to 40∆ base-out with brief and unstable superimposition of targets), and the red lens test (objective angle of 30∆ base-in and subjective angle of 8∆ base-out with intermittent left eye suppression). The patient could not perceive the afterimages needed for the Hering-Bielschowsky afterimage test. An assessment of gross convergence ability revealed that the patient could converge her eyes to a near target, but she experienced diplopia when doing so.

The patient’s pupils were round and reactive to light, and there was no afferent pupillary defect. Slit lamp biomicroscopy revealed no corneal or anterior segment abnormalities. Fundus evaluation revealed pigment deposits in both eyes’ maculae and perimacula areas (Figure 1).

The prognosis for improving the cosmetic appearance of the exotropia with a nonsurgical approach was poor because of (1) significantly reduced bilateral visual acuity, (2) the size (30∆-35∆) of the exotropia, and (3) the presence of paradoxical anomalous correspondence. However, because the patient was highly motivated, we discussed 2 possible nonsurgical approaches: cosmetic prism13 and vision therapy. The patient elected to try vision therapy. Thus, we initiated a trial period of vision therapy to see if we could further develop the patient’s gross convergence ability and teach her “voluntary” convergence (convergence without looking at a near target). We hypothesized that if successful, it might provide her with a strategy to reduce the magnitude of her exotropia when needed. We agreed to a trial period of 5 sessions of in-office therapy to determine whether such a treatment strategy would be beneficial. The patient was instructed to perform pencil push-ups at home for 5 minutes per day, 5 times per week, before her first therapy session.

The patient started her first in-office therapy session 2 weeks after the initial evaluation. The therapy program comprised gross convergence training with the goal of achieving voluntary convergence. Gross convergence training teaches the concept and sensation of converging the eyes, often with the goal of voluntary convergence, which is the intentional convergence of the eyes without looking at a near target.14,15 The patient’s convergence-induced diplopia was used to provide her feedback regarding her eye alignment. Table 1 outlines the therapy program and techniques used at each therapy session.

The therapy program commenced with a pencil push-up procedure but substituting the patient’s finger or a large fixation target for a pencil. The goal was to improve gross convergence ability and encourage kinesthetic awareness (ie, sensation of the eyes) of convergence.14,15 Starting with the target at arm’s length, the patient could converge to 5 cm from her eyes. She could bring her right eye in further when the target was closer than 5 cm, but the left eye would not converge further. When performing gross convergence therapy, the patient reported she was aware of her eyes moving inward and felt a “straining” sensation; she also noted diplopia when converging. The patient was instructed to practice converging her eyes while maintaining a consistent separation of the diplopic images.

Once the patient could converge her eyes and maintain convergence to a near target, the next step was to sit facing the clinician at approximately 40 cm. The patient was instructed to look at the clinician’s face while reproducing the same “straining” sensation that led to subsequent diplopia. The clinician provided the patient feedback regarding her eye alignment (ie, eyes appeared straight, left eye turned outward, or left eye turned inward) while the patient paid attention to the separation of diplopic images and sensation of her eyes when converging. With practice, the patient learned to recognize the distance between diplopic images when her eyes were cosmetically aligned in primary gaze at near. The same training was used for intermediate and far distances. However, at 10 feet, she had difficulty using diplopia for feedback because of her poor vision. Thus, the patient was instructed to imagine looking at a close object and reproduce the “straining” sensation she experienced during the push-up procedure. This strategy helped her maintain cosmetically straight eyes when viewing objects at intermediate and far distances.

Once the patient was proficient at aligning her eyes at near, intermediate, and far distances, we worked on maintaining eye alignment while tracking a moving object approaching her and moving away in primary gaze. She also practiced quickly recovering eye alignment by closing her eyes for several seconds and then quickly regaining alignment after opening her eyes.

The next phase of the therapy aimed to teach the patient to maintain cosmetically straight eyes while performing pursuit and saccadic eye movements. The patient tended to move her head during saccadic eye movements to keep her eyes in primary gaze. She was made aware of her head movements and was instructed to keep her head still while practicing maintaining voluntary convergence when making saccadic eye movements. The patient also worked on moving her eyes into up, down, left, and right gazes while maintaining eye alignment. Down gaze was most challenging; her left eye would drift out slowly over time. The patient learned to correct the spontaneous outward drift by making the object of fixation diplopic using voluntary convergence.

The last training phase focused on maintaining cosmetically straight eyes while the patient was in motion. First, the patient practiced walking toward the clinician while maintaining eye alignment; walking slowly was necessary because she needed to observe diplopia for eye alignment. She also practiced shifting fixation from straight-ahead gaze to the clinician while walking side by side. The patient had more difficulty when the clinician was to her left; she needed to make herself see “more” diplopia for eye alignment.

Throughout therapy, the patient was highly motivated and demonstrated keen observation skills in detecting the separation of diplopic images. She was also aware of the level of strain and “movement” of her eyes. The patient could adjust the separation of diplopic images and the degree of the straining sensation based on the clinician’s feedback on the straightness of the patient’s eyes. The patient diligently practiced each day at home with her friends and family, applying her new eye-alignment skills to daily activities, such as interacting with clients and meeting people in social settings. She also practiced controlling her eye alignment while having her photo taken. The patient completed 3 sessions of in-office training over a span of 2 months, with most of the therapy occurring at home. The patient was instructed to continue practicing at home to maintain or continue to improve the automaticity and stamina of her convergence and return for a follow-up visit in 2 to 3 months.

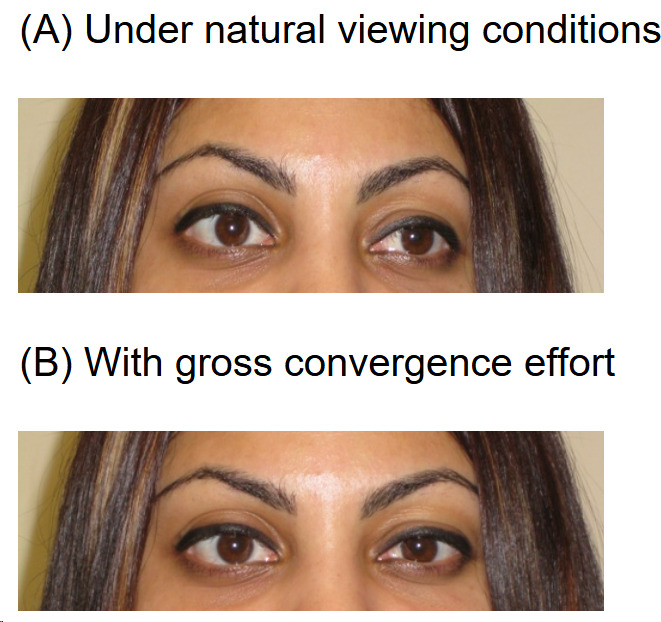

At the 3-month follow-up visit, the patient reported that she could easily align her eyes as needed. She reported that her eyes appeared straight in photographs (Figure 2), and she could successfully maintain cosmetically straight eyes for 30 minutes when conducting an interview, only occasionally needing to look down momentarily if fatigued. Furthermore, she could easily maintain eye alignment when viewing at various distances, making pursuit and saccadic eye movements, and walking. Overall, the patient expressed high satisfaction with the outcome of the therapy.

DISCUSSION

Sensory strabismus is typically a unilateral strabismus resulting from significantly reduced vision in that eye. Poor vision is an obstacle to sensory fusion and has been theorized to potentially abolish the fusion mechanism altogether.1 Our patient did not have the classic presentation of sensory strabismus because she had bilateral vision loss from cone-rod dystrophy with slightly worse vision in one eye. The bilateral vision loss and the asymmetry of visual acuity were both obstacles to sensory fusion.

When managing patients with sensory strabismus, it is critical to identify and treat the underlying cause of vision loss. One should determine whether vision can be improved or restored and whether fusion can be reestablished. In cases in which the strabismus developed at a young age, amblyopia resulting from the strabismus (strabismic amblyopia) may compound the organically caused vision loss, further reducing visual acuity. Unless it is evident that the vision loss in children is entirely from the organic disease, clinicians should prescribe amblyopia therapy to attempt to recover some or all of the vision loss from amblyopia.16,17 When the vision loss is longstanding and irreversible, and reestablishment of fusion is not possible, treatment of sensory strabismus is often directed toward improving the individual’s cosmetic appearance, if desired.

The most common treatment for improving the cosmetic appearance of sensory strabismus is extraocular muscle surgery. The surgical result in this form of strabismus, however, is less predictable than in strabismic patients with normal vision.1 The poor visual acuity and lack of fusion make postoperative ocular alignment often temporary, with reoperations likely.11,12 Botulinum toxin injections have been suggested as an alternative or adjunct to strabismus surgery,18 although high-quality evidence supporting this treatment is lacking.19,20 If the sensory strabismus is small to moderate in size, a cosmetic (inverse) prism (ie, base-out prism for exotropia) before the deviated eye may improve apparent eye alignment because the eye behind the prism will appear to be displaced toward the apex of the prism.13

Vision therapy to achieve normal sensorimotor fusion is not typically considered for sensory strabismus because of the poor potential for attaining normal sensory fusion, which is thought to be the most important prognostic factor for the successful treatment of strabismus with vision therapy.15 Given our patient’s goal of achieving better cosmesis for her exotropia and her high motivation, we attempted a trial therapy program. The program used kinesthetic awareness of gross convergence and diplopia as feedback to improve the cosmesis of the exotropia. After a short period of gross convergence training, our patient could intentionally reduce the magnitude of her exotropia to the point at which it was cosmetically unnoticeable for up to 30 minutes. From the patient’s perspective, this significantly improved her quality of life. It is unlikely that this type of therapy program for patients with sensory esotropia would be beneficial, as it would require voluntary divergence training. Improving divergence is typically more challenging than convergence, making it less likely to yield benefits in such cases.

Strabismus can significantly impact a person’s quality of life, affecting functional abilities and psychosocial well-being.21–23 There are reports that adults with strabismus experience higher levels of anxiety and depression compared with the general population.23,24 Societal attitudes towards those with strabismus can detrimentally affect their employability and social interactions.22 Although normal binocular vision is often the end goal of treatment, it is essential not to overlook the significant impact that cosmetic appearance can have on a person’s psychosocial and social well-being.22,23 One should be cognizant of these quality-of-life concerns and consider them when managing patients with strabismus.

CONCLUSION

This case illustrates the importance of determining the patient’s goal and being willing to attempt novel therapy approaches. Our patient had a specific goal of improving the cosmesis of her exotropia for photographs and certain social- and work-related situations without undergoing surgery. She was not interested in attaining normal binocular vision. Although the prognosis for attaining normal binocular vision was poor because of the poor visual acuity and lack of sensory fusion potential, a novel therapy program improved the cosmesis of the patient’s strabismus and enhanced her quality of life.

TAKE HOME POINTS

-

Eye care providers must communicate with their patients regarding their goals for strabismus treatment.

-

Although sensory fusion status is vital in determining the prognosis for achieving normal binocular vision in patients with strabismus, not all are interested in attaining normal binocular vision; some patients simply want their eyes to look straight.

-

In cases in which the prognosis for achieving normal binocular vision is poor, novel therapy approaches can be considered for patients seeking only an improved cosmetic appearance.